Funny Pictures of Beatnik Hipster Poets

Everyone hates hipsters. Yet we won't stop buying iconic "hipster" accessories, like fixed-gear bikes, vinyl records, and Buddy Holly glasses. As these products are adopted by everyone from investment bankers to organic farmers, hostility towards the elusive hipster grows. After all, he killed authenticity and watered down the counterculture, right?

The real reason hipsters are so easy to vilify, and impossible to identify with, is that they never existed in the first place. The hipster, as we know it, is just an aesthetic disseminated by marketers, a visual style advertised as full-fledged ideology. But the model for this insidious campaign actually came from the first American subculture repackaged by the media: the Beat generation.

"The Beat style was a non-style; it was anti-style. They tried to be invisible, to be existential."

While 1950s America worshiped a cult of conformism, centered on suburban homogeneity and the nuclear family, the Beats weren't buying it. In fact, the Beats were staunchly anti-materialist: No new outfits; no fancy cars; no mortgages; no corporate jobs. Instead, they explored new methods of living and creating art, new ways of understanding existence.

Yet their rejection of the conventional quickly caught the attention of mainstream media. The Beats were transformed into "beatniks," tantalizing America with a superficial version of the underground scene. It wasn't long before companies found ways to sell the beatnik image, recognizing that products could be "cool," too.

Real, live Beats: Larry Rivers, Jack Kerouac, David Amram, Allen Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso (in the hat) at a coffee shop in the 1950s.

The Beat generation initially took its cues from New York's black creative community in the 1940s. "Jack Kerouac was a jazz fanatic and a student at Columbia University in the early '40s, and he used to go to clubs in Greenwich Village and Harlem in between classes, and regularly see the likes of Charlie Parker or Billie Holiday," says Alan Bisbort, author of Beatniks: A Guide to an American Subculture. Kerouac would follow famous musicians like Zoot Sims through the streets of New York to observe their every movement.

Besides an interest in the jazz scene, Kerouac and his cohorts also had an obsession with the illicit underworld of New York. "There was this fixation or fascination, particularly among college-aged kids like Kerouac, with the criminal element, with that sort of seedier side of the big city," says Bisbort. "All those influences fused into this sense of being different, being an outsider, and not being a square, not being a person who has to play by the rules."

Left, authentic Beat style as seen at the Co-Existence Bagel shop in San Francisco in the 1950s. (photo from "The Beats" by Mike Evans) Right, hip style helped to sell products like Apache stockings.

Kerouac is often credited with first using the self-reflexive word "Beat," which he adopted from a Times Square con-man named Herbert Huncke. As Bisbort explains, "One of Huncke's favorite expressions was, 'Man, I'm so beat,' so Kerouac started playing with that whole idea of being beat. Huncke meant it as 'I'm really beat down, I'm so tired, I'm being crushed by the man' kind of thing. Kerouac, being a devout Catholic, also saw it as beatific in the religious sense."

In contrast, "beatnik" was actually a term of derision, coined by Herb Caen for a San Francisco Chronicle article in 1958. Caen's term was originally used to describe the fallout of the San Francisco Beat scene, when suburban kids began pouring in to party on the weekends. Six months earlier the Soviet Union had launched its "Sputnik" satellite into space, and the perceived threat was a hot topic among politicians and the press.

A poster for the film "The Rebel Set" from 1959 capitalizes on the popular beatnik craze.

Though unintentional, the phrase conjured an image of underage Communist dissidents bent on destroying traditional American society. Caen's national syndication made beatnik an instant buzzword, even though the original Beats eschewed the term, preferring to be known as part of the Beat generation or the "subterraneans," after Kerouac's novel of the same name.

In 1959, television viewers across the country were exposed to the division between beatniks and squares by the hit show "The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis." Bisbort describes Dobie Gillis as a "kind of do-gooder, WASP-y, suburbanite kid," whose best friend, Maynard G. Krebs "was a real bona-fide beatnik, who wore berets and played the bongos, and grafted the beatnik image on the American group-mind, so to speak." Krebs' goofy caricature was portrayed by Bob Denver, best remembered for his role as Gilligan from "Gilligan's Island."

Left, Dobie Gillis (in a crew-cut and all-American plaid) and Maynard G. Krebs (in a goatee and dirty sweatshirt) came to represent the dichotomy of '50s America. Right, Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights Books featured publications other stores were afraid to sell.

Levi Asher, founder of the website Literary Kicks, agrees that the mass-media boom distorted the beatnik into a stereotype distinct from the actual Beat lifestyle. "Certainly the Beats caught that wave—magazines loved to take pictures of them. They became a sensation." As America was swept away in a Technicolor fantasy of television and teen magazines, these plain fellows in dark clothes stuck out like sore thumbs. Despite attempts to lie low and drop out, the Beats became larger-than-life.

Following a majorLife Magazine exposé called "Squaresville U.S.A. vs. Beatsville," one letter to the editors aptly expressed the Beats' frustration with their public image. "Beat is not wearing dark glasses and beards and 'talking funny.' It is being; it is a realization of yourself as a separate entity and yet as a part of the whole rhythm of the universal life force…It is a pity that a movement of such scope had to be reduced to the high school skit level."

In 1959, "Life Magazine" contrasted the stereotypes of America's two halves: Squaresville U.S.A. vs. Beatsville (really Hutchinson, Kansas vs. Venice Beach, California).

Besides capitalizing on the beatnik cliché, mainstream media dismissed the Beat generation's creative output. "There's a stereotype that the Beats were a bunch of layabouts, hanging out and drinking wine," says Bisbort. "Maybe they did that, but they also created great works of literature, music and visual arts that we're still enjoying today. It was a hugely fertile time." Yet all the while, Beat writers like Jack Kerouac, John Clellon Holmes, and Allen Ginsberg had their work denounced by censors and panned by popular critics.

These negative responses only made the Beats more visible, with commercial exploitation following close behind. In her memoir Minor Characters, Beat writer Joyce Johnson explains how the media representation quickly shifted to a marketing one. The beatnik stereotype "sold books, sold black turtleneck sweaters and bongos, berets and dark glasses, sold a way of life that seemed like dangerous fun—thus to be either condemned or imitated. Suburban couples could have beatnik parties on Saturday nights and drink too much and fondle each other's wives." Record labels, paperback publishers, and clothing companies used images of wild beatniks to sell this sense of "cool," a word America had never heard before the Beats.

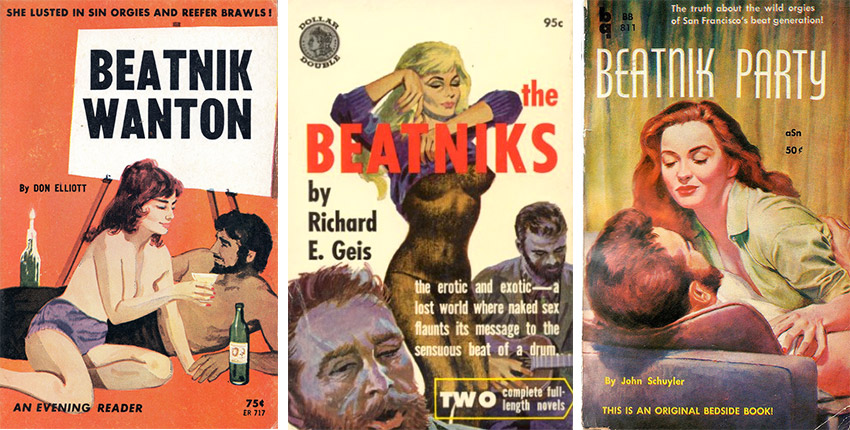

Many pulp paperbacks in the '50s and '60s featured the beatnik stereotype, highlighting licentious sexuality and a drug-crazed mentality.

This hollow beatnik image incorporated elements from a mix of outsider groups: the beret was inherited from the French-infused Bohemian scene of the '20s, the bongos from jazz musicians of the '40s. "I can't recall a single scene in any book by Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, William Burroughs, John Clellon Holmes, Gary Snyder, and all down the list, that contained a bongo drum," says Bisbort. "And yet that is somehow affiliated with the beatnik stereotype." Even Café Vesuvio, a landmark Beat hangout in San Francisco, hired a local kid to sit in the front window and play a stereotypical beatnik for ogling tourists.

Henri Lenoir, owner of Café Vesuvio, stands in front of their tongue-in-cheek ad for a "Beatnik Kit" in the '60s.

So what did the real-life Beats adopt as their visual iconography? Bisbort says that "the Beat style was a non-style; it was anti-style. They tried to be invisible, to be existential." In addition to rejecting the superficial, this pared-down aesthetic connected directly with the group's anti-materialist perspective. Bisbort explains the Beats were "a sort of pinprick at the side of America saying, 'You think you're all great. You won a World War and everybody's moving to the suburbs and Levittown and building these grotesque houses that all look the same.' That's not happiness."

By the year 2000, American consumer culture and media coverage had grown much more complicated, particularly given the Internet. Media cycles accelerated to the point that alternative trends were analyzed and marketed the instant fringe communities adopted them. Just like the beatnik, the modern hipster was co-opted by brands looking to use rebellion to sell products.

In 2010, Mark Greif wrote that the hipster "aligns himself both with rebel subculture and with the dominant class, and thus opens up a poisonous conduit between the two." In fact, this linking of non-conformist symbols to mass consumption is pure marketing; the hipster only exists as a superficial consumer identity, easily derided for its emptiness.

2003's "Hipster Handbook" distilled various different identities into a set of visual signifiers.

A closer look at the hipster aesthetic reveals an amalgamation of emblems taken from various subcultures: the urban farming and locavore food movements, the freegan lifestyle, DIY and handcraft entrepreneurs, the Occupy movement, and artist communities. Much like the Beats before them, these real-life countercultures celebrate principles of minimal consumption, sustainable living, and authentic experience, searching for ways to live outside the mainstream economy.

But for Urban Outfitters or the Gap to sell alternative-chic, the trappings of these groups have to be marketed to the mainstream, distancing fashion from ideology. Greif identifiedVice Magazine, Alife, and American Apparel as the original and most visible emblems of this developing style, three labels that staked their financial success on selling an idea of rebellion.

As with the hipsters of today, America was simultaneously fascinated and repulsed by the beatniks.

Objects associated with outsider status quickly permeated major retailers, and big-box stores like Target and Walmart began stocking "vintage wash" denim and reproduction concert tees. Once these iconic items spread among the American mainstream, they lost their original context and became a part of our generic consumer environment.

Which brings us back to why we hate hipsters. In an article forTheL Magazinein 2010, Jonny Diamond argued that this repackaging of authentic signifiers for mainstream consumption is directly linked to hostility toward perceived hipsters. This animosity is generally directed at individuals who embrace elements of the aesthetic, regardless of their creative, political, or philosophical beliefs. As a result, celebrities like Wes Anderson, Dave Eggers, Miranda July, or the band Animal Collective are often denigrated as hipsters, criticized for the shallowness of their work.

Such hostility may have also had an impact on the Beats: When Kerouac was finally "hoisted up on a pedestal and declared king of the beatniks," as Alan Bisbort describes it, the entire movement had become an empty stereotype, even among those who identified with it. Levi Asher thinks Kerouac was ultimately destroyed by public criticism and media caricature, which drove him to alcoholism and an early death at age 47.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, founder of the iconic City Lights Books in San Francisco, provided an insightful warning in his 1958 poem "Junkman's Obbligato": "By the time they print your picture in Life Magazine, you will have become a negative anyway, a print with a glossy finish. They will have come and gotten you to be famous, and you still will not be free."

Jack Kerouac listens to himself reading on the radio in 1959.

mcfarlandwassithe.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/cool-for-sale/

0 Response to "Funny Pictures of Beatnik Hipster Poets"

Post a Comment